|  |

By Greg Niemann

A bit of France in Baja

The sparkling Sea of Cortez looming in the distance is a refreshing sight after miles and miles of mostly barren land. However, first-timers driving down Highway 1 are often disappointed when they arrive at that first seaside town.

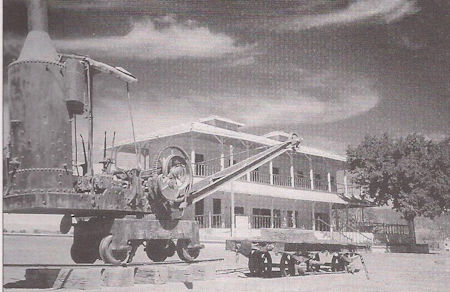

Instead of a broad sandy beach and a laid-back thatch-roofed village, travelers find a rocky shoreline, lots of old smelting and mining equipment, and a dark soot that seems to permeate everything. They have arrived in Santa Rosalía, an old mining town where a French company created not only one of the world’s major copper-producing mines, but a company town with a decidedly French flavor.

The town has rows of wood frame buildings, balconies and corrugated tin roofs that look more European than Baja. Even the prefabricated metal church, that was designed by Alexander Gustave Eiffel (he of Eiffel Tower fame), was shipped from France.

John Steinbeck once noted that the town looked “built” whereas: “A Mexican town grows out of the ground.”

Everything about the place was company-built and company-run: the homes, the smelters, the stores, the hotel, the railroad, the docks, and the ships. The product of the smelters, called copper matte, was shipped to Guaymas across the Sea of Cortez, then by rail to New Orleans and finally as ballast in steamers to France.

It all started in 1868 when copper ore was discovered by rancher Jose Villavicencio. The original ore appeared as small round blue and green concretions or balls (boleos). Legend has it that Villavicencio was paid only 16 pesos for his discovery.

The House of Rothschild

Some of these ore samples found their way to France and caught the attention of geologists of the House of Rothschild, who decided to finance the mining operations.

In 1884 and ‘85, they formed the Compagnie Boleo (El Boleo Copper Company) and bought up the holdings of a number of independent miners. The Mexican government granted a 200-square-kilometer claim to the company in 1885.

Later the company ownership became both French and Mexican and the name was changed to Boleo Estudios e Inversiones Mineras, S.A., but it was still referred to as El Boleo.

Getting workers to such a remote location was a problem. Some Yaqui Indians were brought in from mainland Mexico. The company recruited about 2,000 Chinese workers, assuring them they could plant rice when they came to work at El Boleo. Most left when they discovered that rice wouldn’t grow in such a desert climate.

Mine workers were also recruited from nearby villages. Mulegé, 38 miles to the south, lost more than its workforce to El Boleo. Mulegé was originally named after its mission, Santa Rosalía de Mulegé. The new company town to the north appropriated the first part of the name as well as many of its citizens; neither was ever returned.

At one time the company controlled more than 2,000 square miles of surrounding country.

An ugly soot problem

They erected a huge copper smelter that deposited a dark soot all over, turning everything black and endangering the health of the inhabitants. Early on, to remedy some of the soot problem, El Boleo built a horizontal duct from the smelter in town to a huge chimney stack half a mile north. It allowed the citizens to breath, but did not enhance the sooty character of the town.

Many miles of tunnels were dug, making the ground under Santa Rosalía more porous than Swiss cheese. They built 18 miles of narrow-gauge railroad track to move the ore. Water was another problem. They had to pipe fresh water in from the Santa Aqueda oasis, about 10 miles away.

By the early part of the 20th century, Santa Rosalía had become one of the world’s major copper-producing areas.

The original director of El Boleo was Monsieur Cuminges, the geologist who examined the first deposit. After him were the directors Monsieur La Farge and Monsieur Michot. Then Mr. Nopper was director for 35 years before turning the helm over to Monsieur Pierre Scalle.

It is said that Monsieur Michot was the most generous with the company’s money. Along with establishing many mining safety measures, he dug numerous water wells, established ranches and farms to furnish the miners and their families with food, and constructed roads.

The company town straddles two mesas, with all the French mining officials housed on Mesa Norte. On the South Mesa lived the Mexican officials and soldiers. Most of the workers lived in the business part of town, which was laid out on straight streets in the arroyo between the two mesas.

The high-grade ore was mined out by 1930, but the company stayed in existence until it finally closed in 1953. A couple of years later, a Mexican company resumed operations. Another company, Compañía Minera Lucifer, was organized around the same time to work the manganese deposits in the area. Both those companies operated on a much smaller scale than the legendary El Boleo. Mining continued until 1985, when the smelter was finally shut down on the eve of the town’s 100th anniversary.

The mining saga continues

Enter Baja Mining Corporation. With an eye toward reigniting the Santa Rosalía project, that same year (1985) John Greenslade of Vancouver, Canada established the Baja Mining Corporation. He partnered with Korean investors to develop the Minera y Metalúrgica del Boleo mine in Santa Rosalía.

The company was incorporated and funded throughout the 1990s, and by 2010 had raised $1 billion U.S., eventually capitalizing at almost $2 billion. Originally El Boleo had been scheduled for copper commissioning in 2012, but finally started mining in early 2015, way behind schedule and $750 million over budget.

In the first half of 2016, Baja Mining recorded a net loss of $1.6 million, and the company admitted the Boleo mine project had provided no source of income, only losses. With working capital of just $54,000 at the end of the first half of 2016, Baja Mining needed an infusion.

The Vancouver-based company struggled for months to keep the project alive until Korea Resource Corporation (KORES) bought a majority stake, Baja Mining now owning only less than 10% of Boleo.

Baja Mining Corp. was delisted from the Toronto Stock Exchange in 2014, but its shares started trading on the Toronto Venture Exchange three days later. After the value of shares fell to about $0.01, Baja Mining Corp. announced a 1-20 share rollback (consolidating its 340.2 million common shares to 17 million) and a name change.

Now called Camrova Resources Inc. the Canadian mining company (through Minera y Metalúrgica del Boleo), currently owns a 7.3 % interest in Santa Rosalía’s Boleo copper-cobalt-zinc-manganese project. The Boleo Project is projected to annually produce approximately 30,000 metric tons of copper, 700 metric tons of cobalt and 10,500 metric tons of zinc sulfate. The commissioning phase of the processing plant has been declared completed and as of November 2017, they are actively seeking solutions to improve cash flow.

All I know is I am not investing again. I lost enough as it was because I really like Santa Rosalía and the magic word Baja prompted me to invest.

French influence lingers on

There would be no Santa Rosalía were it not for El Boleo. It took dedicated efforts by the French to make their influence upon the distant Baja shore.

Today the most important thing about Santa Rosalía is the ferry to Guaymas on the mainland. The nine to ten hour crossing on the small (120 foot) ferry leaves Santa Rosalía Wednesdays and Fridays at 8:30 a.m., and on Sundays at 8 p.m. Arrivals from Guaymas are on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. The ferry does not run in windy, choppy water.

I find the town a delight. The unique European architecture may seem incongruous in a desolate corner of Baja, and perhaps therein lies its attraction. It’s a wonderful walking town, up the narrow streets on one side of the arroyo and down the other, with occasional side jaunts onto the mesas.

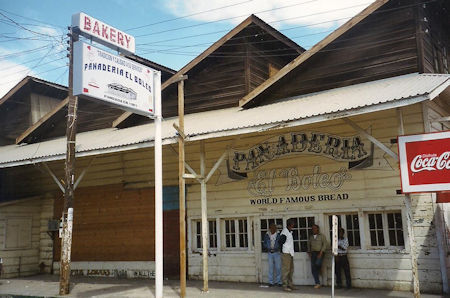

Along with the incongruous Eiffel church (Iglésia de Santa Barbara), there is the charming and historic Hotel Francés on the North Mesa (1886 and still in operation), the Hotel Central and the popular Panadería El Boleo, both in the heart of town.

I always find myself waving at little old ladies sitting on broad verandas or old wooden balconies with corrugated tin roofs. Or smiling at attractive young Mexican girls whose features are more European, as they contain varying degrees of French blood.

Few people would think of the House of Rothschild when they think of Baja. But they haven’t been to Santa Rosalía, where a little bit of France has lingered for years. Just do your homework before you invest – maybe it will be a winner this time.

About Greg

Greg Niemann, a long-time Baja writer, is the author of Baja Fever, Baja Legends, Palm Springs Legends, Las Vegas Legends, and Big Brown: The Untold Story of UPS. Visit www.gregniemann.com.

Good seevice have use baja bound for many years good price....

If you are going to Mexico Baja Bound is excellent. Buy online, good price, good quality. Fast and...